July 18, 2024. The 1980 treaty on international child abduction is now in force in 103 countries and in the midst of an expansion campaign throughout Africa. Meanwhile, a UN decision to protect a Chilean-Spanish boy with autism from being ‘hagued’ has been silenced for two years in Chile and beyond.

by Patrícia Álvares, for El Salto – July 18, 2024*

The most ratified treaty in the world has been cancelled, at least in Chile, where a ruling on the Convention on the Rights of the Child has been ineffective for two years. Nothing has happened since the guardian Committee at the United Nations (UN) questioned the country for violating the human rights of a Chilean-Spanish boy with autism. The media in the country and beyond is behind this silence, as the work of the hague papers, a global network of journalists, attests.

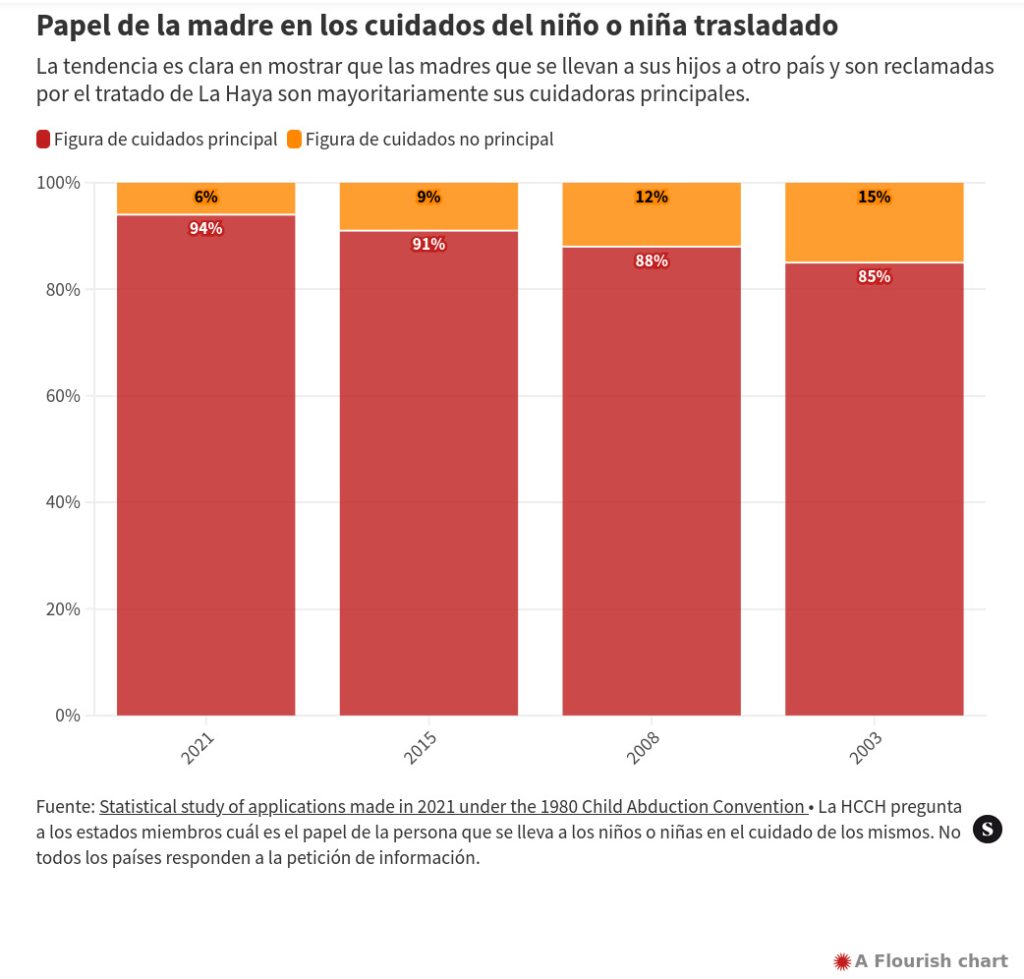

Around 3,000 children and adolescents who travel to another country each year are considered victims of international child abduction by a parent. In 75% of these cases, the children are claimed as victims by the male parent, and in 94% of these cases the parent making the claim is not the primary caregiver according to data compiled by the Hague Conference (HCCH) in its latest report from 2021.

The 1980 Hague Convention provides a protocol to trace children and provide their immediate return. In the process, an average of six mothers a day are accused of abducting their own children, 94% of whom have custody and who are the primary caregivers. This adds up to one mother every four hours, at least 15,000 in the last decade, all of them foreigners.

These are women who are particularly vulnerable because of their migratory status. One of them is the Chilean, Valentina, whose first-person story is part of this journalistic collaboration. In June 2022, the resolution of the UN Child Rights Committee questioned a ruling by the Chilean Supreme Court that determined the return of Valentina’s son to Spain despite his condition and health reports that recommended otherwise. Two years later, however, the Chilean court’s ruling remains in force despite the UN decision.

“It’s a decision that must be complied with by the Judiciary, so it is complicated for the Executive to intervene,” the Uruguayan, Luis Pedernera, told the hague papers. He is one of the UN Committee’s 18 experts in Switzerland who signed the verdict that questioned the Chilean decision. The situation is not helped by “the UN’s liquidity crisis,” which has driven the Committee to cancel an entire week of sessions at the end of May. “There is a backlog of cases and a lack of staff,” Pedernera added.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), responsible for each convention’s committees, told the hague papers that “the follow-up on the case is still on-going” and that “its evaluation report will be made public” once input from both parties is concluded. When asked about estimated dates or possible guarantees for the mother and child, the Office did not respond.

Protected by the UN and persecuted by the State, the mother and her now 8-year-old son remain hidden as they wait for their country to execute its international obligations and recognize her child’s endorsed rights. But while the police continue to hunt them in order to enforce the Hague agreement in violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, Chilean authorities pose for a photo in the Dutch city named after the treaty. Among them, the Director of Legal Affairs for the Foreign Affairs Ministry, Claudio Troncoso, and the Chilean ambassador to the Netherlands, Jaime Moscoso Valenzuela, who met this month with Christophe Bernasconi, the Secretary General of the Hague Conventions’ oversight organization, the HCCH. During the meeting, the European chief offered the South American country to contract more treaties from their menu in private international law, as announced by the HCCH on its social networks.

Two conventions in context

Known as the most ratified treaty in the world, the Convention on the Rights of the Child turns 35 years old on November 20. The United States is the only country out of the 195 recognized States in the world that has not signed it. Each UN treaty has its corresponding central body. The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is the one responsible for ensuring the protection of children and adolescent human rights as enshrined in the 54 articles of its Convention.

The United Nations OHCHR explains that, “through ratification of international human rights treaties, governments undertake to put into place domestic measures and legislation compatible with their treaty obligations and duties.” Thereafter, “mechanisms and procedures at the regional and international level” are established so that anyone can report unresolved human rights abuses in judicial processes within the signatory countries, as Yohana Cornejo, Valentina’s legal representative, did when she denounced the Supreme Court ruling in the case of this woman and her son.

“The Convention on the Rights of the Child has been ratified by all countries except the United States, while the Hague Treaty on Child Abduction has 103 ratifications.”

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, initially signed by only Canada, France, Greece and Switzerland in 1980, has also become a star of international law. It has 103 signatories and continues adding new ones almost half a century later. It is governed by the Hague Conference on Private International Law (also known as HCCH), an intergovernmental organization responsible for some 30 other conventions named after the Dutch city where it has been based since 1893.

Instead of centralized treaty committees, the HCCH works directly in the signatory countries through so-called central authorities. Each country must designate its own as a focal point for direct contact to “cooperate with each other and with the competent authorities in their respective territories to secure the prompt return of children,” according to Article 7 of the Convention on International Child Abduction. They are State officials, trained by the HCCH to serve its conventions.

Two conventions in conflict

What is unprecedented about the UN ruling, beyond the fact that the system addressed the Hague Convention for the first time, is that it acknowledged flaws in its application. Until then, the HCCH Convention had been validated by the UN treaty in a specific article on international child abduction.

Other related complaints that have reached international human rights systems have reinforced the treaty’s mandate on the prompt return of children as being in their best interest without qualification.

International lawyer and consultant Edward Pérez, a PhD candidate in human rights at University College London, responded to the hague papers from England. He considers the UN decision a welcome source of guidance for judges in the limbo between the two human rights conventions and private international law, a very specific discipline that covers the Hague Conferences.

“It is desirable that local courts adopt this position and refrain from ordering automatic restitution to ensure that a legal solution to the case doesn’t result in human rights violations,” said the Venezuelan consultant, who also holds a master’s degree in international law from Cambridge University.

Among The Hague international network of judges, however, the historic ruling may be forgotten, as in Chile. This is demonstrated by the Rio de Janeiro Charter that resulted from the first Latin American and Caribbean meeting of liaison judges in the Brazilian city this past May. Liaison judges are the central judicial authorities for direct contact with their peers in other countries and are referees of the Convention in their respective jurisdictions. They are trained by the HCCH.

“The judges of the international network of The Hague, who met in Rio de Janeiro in May of this year, made no reference to the historic ruling of the Committee on the Rights of the Child regarding the case in Chile.”

The Charter’s only mention of human rights is limited to reinforcing the concern with speed. The judges consider that “the measure that best serves the best interests of the child, in the case of illegal transfer or wrongful retention, is the determination of the child’s immediate return, as provided for in the Convention (art. 1, paragraph ‘a’)”, and supported by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).

The IACHR’s first ruling on child abduction in 2023 was drafted in a session presided over by none other than a former liaison judge, the Uruguayan Ricardo Pérez Manrique. The ruling focused on the need to speed up judicial proceedings according to the six-week deadline set by the Hague, a timeframe that very few countries manage to meet.

While the speed of the process favors the “automatic restitutions” referred to by the Venezuelan expert in London, also a former lawyer at the IACHR, the UN Committee stressed in its resolution that “international restitution must be in accordance with the obligations derived from the Convention on the Rights of the Child” as a whole, that is, not only under the Hague’s Article 11 that validates the private international law treaty.

Maurizio Sovino Meléndez, director of the unit on abuse and sexual offenses against children at the Chilean Public Prosecutor’s Office, regretted that the Inter-American court’s ruling did not mention the UN opinion. “The Court lists a set of norms, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the European Court of Human Rights, but it could have made a nod to the Committee,” he said in an interview with the hague papers.

“It is odd because, although they are different human rights bodies, the Court could have addressed recent pronouncements at the American level, such as the Chilean one, to take into consideration in these cases,” added Sovino-Meléndez, who also holds a master’s degree in international and criminal law.

As for the HCCH, the decision by the Committee on the Child yielded a couple of paragraphs in the treaty’s 8th review conclusions in October 2023. Its content draws on convenient and out-of-context snippets from the UN resolution, supplemented with fragments from HCCH’s own guide for judges.

What is happening in Chile could become a case similar to the one in Paraguay, where the mother fled with her son after being ordered to return him to Argentina. It took eight years before Interpol found them, but the conditions for repatriating the grown child were no longer met. The paradox is that Valentina has the support of the UN, and her country has a regional precedent. There are two conventions and two international systems in conflict.

Silence gives consent

What will happen to Valentina if the police arrive before the UN reaches a solution? The Uruguayan social worker, Andrea Tuana, provides an answer, “we call them snatchings”. Armed agents, in movie-like operations, take crying children from their mothers’ arms in front of everyone. There are records of this happening in Chile, New Zealand , Brazil, France and Uruguay, to name a few.

Far from the “safe return” prescribed by the treaty, these are institutional and surprise returns to prevent mothers from fleeing with their children after the final ruling or because they have already done so. “It is state terrorism,” says Tuana. Director of the organization El Paso. Tuana also supports mothers in migration contexts through the International Network of Uruguayan Women Victims of Violence Abroad (RIMUVVE).

What happens next, nobody knows, neither the judges, nor the press, nor many of the mothers who end up unable to contact their children once they are taken away at the request of the fathers. These are fathers who in 94% of cases did not previously take care of their children on a daily basis in their home countries. “There is no best interest of the child, only of the father,” says the promoter of Rimuvve.

“Far from the “safe return” prescribed by the treaty, the Hague Convention facilitates institutional and surprise returns to prevent mothers from fleeing with their children after the final ruling or because they have already done so.”

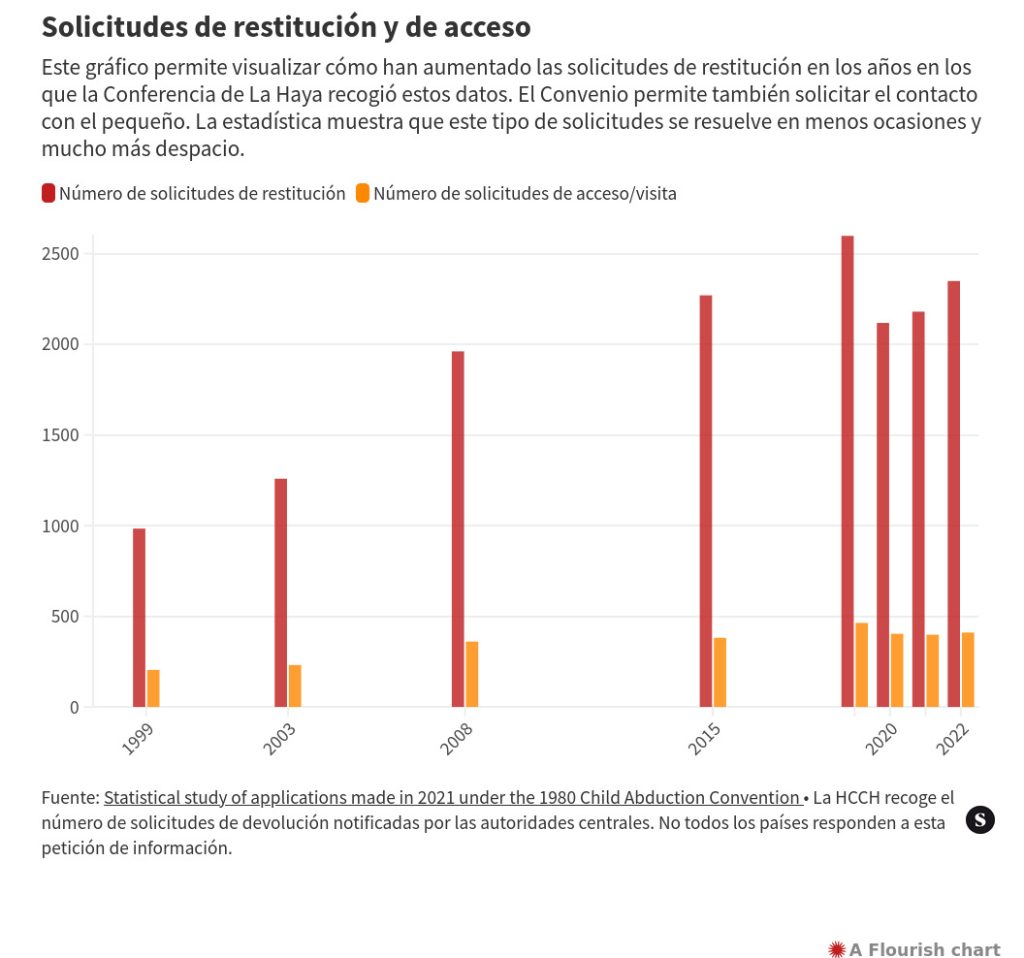

The right of access or contact, for both parents and children, is also provided for in the Hague Convention. Unlike restitution, however, ensuring contact with children does not require speed, compliance or as much attention. In Chile, for example, 17 processes to repatriate children were completed in an average of 166 days in 2021, that is, less than six months. Meanwhile, the only four procedures to maintain the link between parents and children at a distance took more than twice as long, with an average of 446 days, or one year and three months, according to the latest official statistics.

There are worse cases. It took Iceland 560 days, a year and a half, to resolve just two requests for contact. At the same time, seven return requests took 128 days to resolve, an average of four months. The country resolves more than three times as many cases in almost five times less time when it comes to sending children to mostly male parents who did not always care for them before. On the other hand, Spain has not even allowed parents to claim their rights in court. Its central authority directly rejected the 13 requests received in 2021 to contact children who are in its territory without one of their parents.

Under pressure only

Almost 50 years later, the 1980 Hague Convention is now in force in 103 countries and counting. The HCCH itself has made explicit its efforts to extend it to Africa. Botswana and Cape Verde joined in 2023.

Experts consulted by the hague papers on three continents agree that recognizing the rights of Valentina’s son would mean recognizing that the Convention is failing. And if it fails, almost 3,000 children a year would be at risk of institutional abduction, of being uprooted or losing full contact with the person who has cared for them throughout their lives. Some 20,000 children may have already suffered these outcomes in this century. Complying with the UN ruling would legitimize the growing warnings from organizations, studies, women, parliaments, governments, and courts.

Sovino-Meléndez believes that Chile has a good track record of complying with international human rights rulings, although he believes that the courts may have more weight than the United Nations system. Meanwhile, Pedernera assures that “the petitions unit is excellent, but they are overwhelmed”, and though he has taken the case “on his shoulders”, there should be more pressure.

“Norwegian professor Tone Linn Wærstad, a professor of private international law at the University of Oslo, argues that ‘being alert to potential collisions’ is important but complex.”

Applying pressure is also the path indicated by the Norwegian professor Tone Linn Wærstad, a leading expert in private international law at the University of Oslo. Her studies have contrasted human rights with the Hague Conventions. Contacted by the hague papers, Tone argued that “being alert to potential collisions” is important but complex.

According to Tone’s study, ‘Harmonising Human Rights Law and Private International Law‘, identifying such “collisions” and resolving them reveals an interaction that has not yet “been the subject of adequate legal analysis”. Furthermore, although human rights should theoretically prevail, the professor highlighted that “the international system for monitoring and sanctioning the human rights obligations of the State-parties is quite weak”.

“Often, respect for and compliance with human rights obligations depends on the will of the national system itself and pressure from civil society,” she stressed.

*Originally published in Spanish by the Spanish news outlet El Salto, this piece has been written by journalist Patrícia Álvares and translated into English by Diana García.