July 18, 2024. Women’s groups affected by the gender-neutral application of the Hague Convention made their testimonies known to the treaty’s top officials at a forum held in South Africa in June.

The participation of groups of mothers in a forum of the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH), who are affected by the application of one of its conventions, one that does not include a gender and child perspective, is unprecedented, explained Ruth Dineen to El Salto about the Forum on Domestic Violence and the Operation of Article 13(b) of the 1980 Child Abduction Convention that took place between June 18 and 21 in South Africa.

Dineen is the international coordinator of the Hague Mothers project, part of the Filia Foundation in the United Kingdom, and one of those responsible for ensuring that the experts gathered at this forum heard more than a dozen testimonies from women who have been criminalized or found themselves trapped in the countries of those who have committed violence against them or their children. They are the “hagued mothers”, women who have learned what this treaty is about through international search warrants and loss of custody.

The “Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction”, convened at The Hague on 25 October 1980, otherwise known as the Hague Convention, has as its stated aim to ensure the immediate return of children wrongfully removed or retained under the terms of this convention from one country to another, and to ensure that custody rights are respected. What this convention prescribes to achieve is the immediate return of a child to the situation prior to the transfer, without taking into account any context, any documentation that could clarify the reason for the transfer and without listening to the mothers or the children – something that the Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, Reem Alsalem, warned about in a 2023 report .

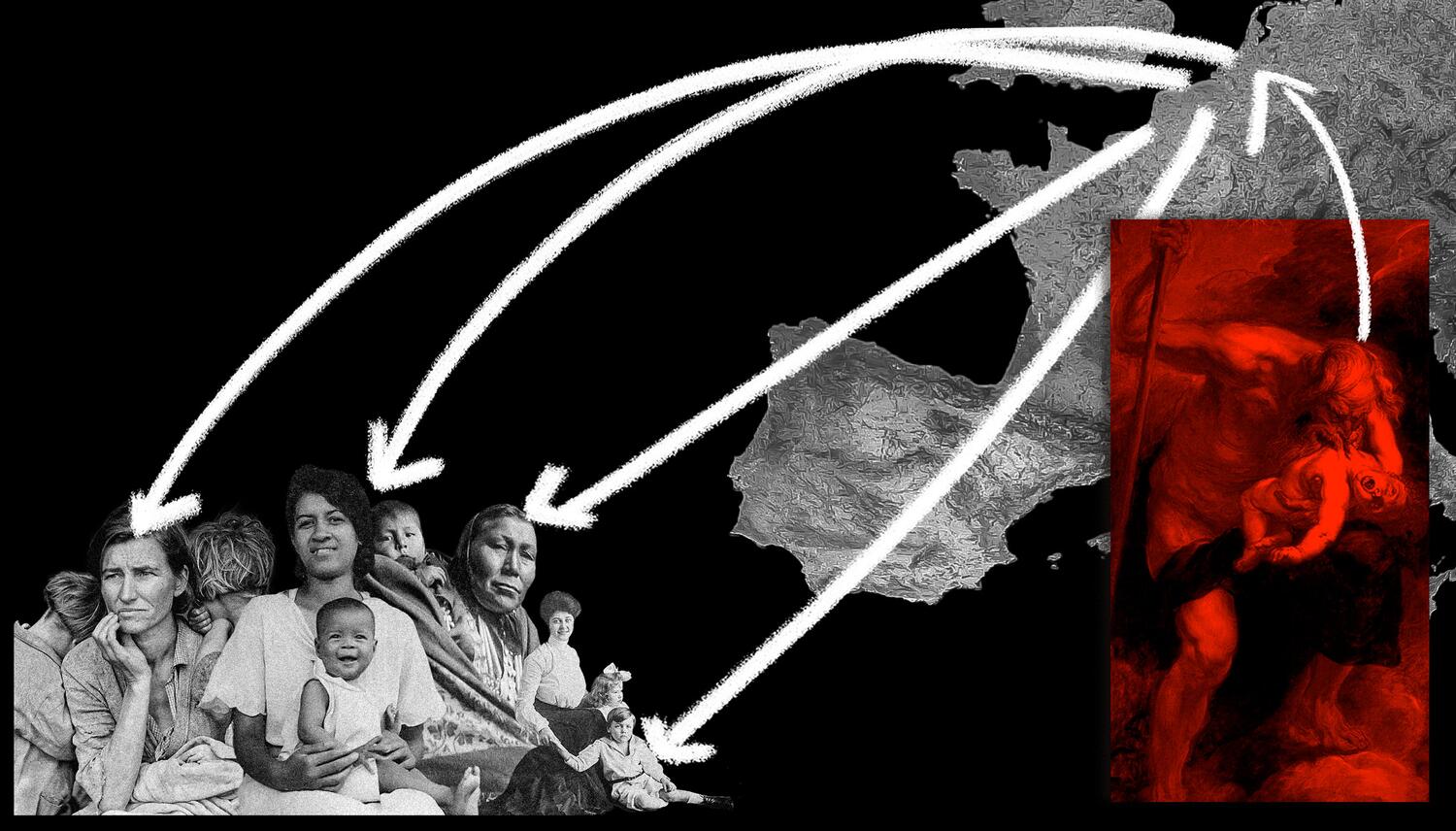

Around three-quarters of cases brought under the Hague Convention are against the mother, who is often fleeing violence, according to a report by the special rapporteur on violence against women, Reem Alsalem.

According to data collected by Reem Al Salem in this report, around three-quarters of the cases brought under the Hague Convention are against the mother, who is usually the primary caregiver and who in many cases is fleeing domestic violence or trying to protect her children from abuse, says the report, citing as its source the seventh meeting of the Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the 1980 Hague Convention on International Child Abduction and the 1996 Hague Convention on the Protection of Children held in October 2017.

Despite the fact that the agreement provides for exceptions—for example, the article 12 exception of a child “now settled in its new environment”, and the article 13(b) exception if “there is a grave risk that his or her return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation”, which was the primary subject of debate in the forum—these exceptions are hardly used.

The convention is being applied “relentlessly.” This is the adjective Ruth Dineen used when she reflected on why mothers affected by the 1980 Convention have only started organizing themselves in recent years. The Hague Mothers Project of the Filia Foundation that she coordinates was created in 2022, and other groups that participated in the forum have only been in existence for five years.

Dineen explained that first of all, The Hague cases against mothers are statistically few, so there has not been much knowledge about them. Secondly, the media has not paid attention to this problem, and, although Dineen did not mention it, a third factor involves the great social changes of the last decades, during which the mobility of citizens around the world has increased considerably, making international families increasingly common. This has accelerated a change in the profile of the “taking parents”, parents who move their children from one country to another without the permission of the second parent.

Ruth Dineen (Hague Mothers Project): “The testimonies moved the Secretary General of the HCCH, Christophe Bernasconi. I think it was the first time he became aware of the problem.”

For Dineen, the June meeting marked a paradigm shift, not only because the Secretary General of the HCCH, Christophe Bernasconi, made it easier for all parties to be heard, but because Bernasconi himself agreed to meet with groups of mothers. “Obviously, he was moved by the testimonies; I think it was the first time he became aware of the problem,” explains Dineen. Bernasconi made a verbal commitment to the mothers to follow up on the issue through a forum on gender violence. “All the credit goes to the mothers who wrote to him, their voices made the difference,” she said.

For the South African forum, Filia prepared a protocol proposal in collaboration with another collective of mothers, Revibra Europa, a group founded informally in 2012 that in 2018 was established as a support organization for Brazilian mothers affected by situations of gender violence in Europe. The protocol encourages participants to actively listen to mothers, to consider their situations of trauma, and to be mindful of the language they use, for example, to not automatically label these “taking parents” as “abductors”.

“We were very concerned that we were encouraging women to participate in something that would re-traumatize them, so we created this basic protocol, which was shared with all attendees.”

Mothers Revolution Recommendations

But Filia and Revibra were not the only organizations present at the forum. Participants also had access to the report produced by the Mothers Revolution organization. This collective was founded in 2018 to provide protective mothers with support services such as legal advice, media strategy or trauma counselling, , as its director Geerte Frenken explained to The Hague Papers, especially in cases involving mothers from the USA and in cases where the Hague Convention is used.

From her own experience and from the experience she has gained through the numerous cases that are referred to this organization, she explained that “since the treaty came into force, Article 13(b) is rarely applied in cases of domestic violence and child abuse.” The Hague proceedings take place within a very short period of time – between six weeks and a few months, “and most children are ordered to return to their country of origin, and to what the law considers their ‘habitual residence’.”

Geerte Frenken (Mothers Revolution): “Fathers’ rights advocates often advise them to allow mothers to take their children back to their home country and then file a petition in The Hague alleging abduction.”

“Advocates for fathers’ rights often advise them to allow mothers to take their children back to their home country and then file a petition in The Hague alleging abduction, as they know that this strategy usually results in fathers winning their case in The Hague and subsequently obtaining a so-called quick order in their own country granting them full custody of the children and ending contact between mother and child,” she explains.

Geerte described what in Spain are known as “arrancamientos (uprootings)” – forced separations of a mother and her child: “Children are abruptly and sometimes violently removed from their protective mothers by SWAT teams. Some of these mothers face long-term imprisonment, while in other cases they have been murdered by their abusive ex-partners,” the director of Mothers Revolution stated. “The protective measures provided in some Hague rulings are rarely applied once children return to their habitual residence,” she went on to explain, “so the vast majority of children in The Hague are returned to the country of habitual residence and into the custody of their abusive parents, with dire consequences.”

Although there is a guide to good practice in applying the Hague Treaty that aims to prevent such devastating proceedings and their results, “it has not been followed in any of the numerous cases that our organization has observed over the last decade.” Not only that, but judicial staff, confronted about their failure to comply with this guide, respond evasively: “they tell us that it is not a law and therefore they do not have to comply with it.”

During the forum, Geerte presented the report “Violence against Mothers and Children through The Hague Convention: Causes and Solutions”, which exposes this situation. In this document, the organization makes a series of recommendations: prohibiting parents from invoking the Hague Convention when there is proven abuse, assessing the situation when abuse of the mother or child is alleged, involving experts in the assessments or listening to the children are just some of the proposals. One of the key measures and recommendations also has to do with language: the study values replacing the decision based on the “habitual residence” with a decision based on the “habitual parent”, that is, assessing who is the primary caretaker of the child, as well as prohibiting the use of force when children are finally separated from their mothers.

Frenken is aware that not all attendees at the forum shared the same views and that among them were some judges who apply sexist biases or parents who use the treaty to gain an advantage over the other parent.

“We heard many people in prominent positions oppose treaty reform and some presentations seemed to focus on reputation management, with statements that the treaty works well as it is and does not need reform. Others seemed even more disconnected, claiming that protective mothers use the Hague treaty to ‘forum shop’. Some acknowledged that the interpretation of Article 13(b) could be improved but argued that the article itself cannot be rewritten due to the lack of an amendment clause in the Treaty,” Frenken explained. “Furthermore, there were arguments that even if an amendment were possible, it would be impossible to get all ratifying nations to agree…however, it was clear that many ratifying nations have already created their own sub-articles of 13(b) at the local level to guide their judiciary, which is a prima facie indication that the article within this treaty does not operate adequately and consistently across countries.”

Although this conclusion sounds pessimistic about possible changes in the implementation of the treaty, Frenken agreed with Dineen that the mothers’ voices resonated with those in attendance: “Amidst many rather embarrassing presentations, the powerful victim statements made by several Hague Mothers brought the conversation back to reality like a thunderous flash of lightning and even the most stoic facades began to crack,” she explained. “It was heartening to see some judicial officials genuinely and courageously express how deeply moved they were by these harrowing stories, and many admitted that they had never met with the Hague Mothers or their torturous experiences first-hand, nor faced the terrible and sometimes deadly consequences of the Hague rulings.”

A letter from Japan

In addition, the forum participants received a letter from the Japanese mothers’ collective All Japan Women’s Shelter Network. In their letter, which they addressed to the forum participants, they expressed their concern about the “serious risk” determination of the Hague Convention in Japan and around the world.

“Japan’s Domestic Violence Prevention Act, enacted in 2001, defines domestic violence broadly, including situations where there is no physical violence or imminent danger to life. In addition, under the law, which was revised and went into effect last April, acts of psychological, sexual and economic domestic violence are also covered by restraining orders. The Child Abuse Prevention Act also defines the situation of witnessing and living with domestic violence as an act of psychological abuse of a child that must be intervened and protected by government authorities, even if the child himself or herself is not physically harmed,” the statement said.

A group from Japan asked in an open letter that the standards of the Istanbul Convention be taken into account when applying the Hague Convention

The Japanese mothers called for consideration of the Istanbul Convention, which they cite as a global standard for violence against women since its creation in 2011 — and which is used as an international reference alongside the 1994 Belém do Pará Convention. “Article 13(b) should be based on the same criteria,” they said. “We believe that Article 13(b) should be revised, or the interpretation should be changed to clearly state that domestic violence, including emotional, economic, social, sexual and other types of violence, as well as child witnesses, are included among the forms of abuse,” they stated in their letter. “We also believe that a survey should be conducted to determine whether domestic violence and child abuse have been underestimated in the implementation of the Convention.”

Next steps

Mothers’ groups hope that their participation in the South African forum will mark a turning point. Despite the difficulties in reforming the convention, Frenken explains, there are other ways.

Australia, the UK and Brazil have all suggested they might consider training for judges, says Ruth Dineen, who believes the best way forward is to approach countries that have signed up to the convention on an individual basis. “For example, in Australia, the attorney general has made some internal changes that have not been effective so far… but the intention is right,” she says. And if this works in Australia, other countries might want to implement it as a matter of policy.

About this article and The Hague Papers project

This article is the result of the joint work of Mónica Aguilera (Chile), Patrícia Àlvares (Uruguay) and Patricia Reguero, from El Salto. In addition to this report, this Special Hague Convention also includes the articles A child and his mother have been criminalized for two years due to a ruling that dictates their return from Chile to Spain and This is the convention on child abduction that the UN is questioning due to the case of a Chilean-Spanish child , prepared within the framework of The Hague Papers , a collaborative journalism project to collect information on the consequences of the application without a gender perspective or a childhood perspective of the Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, convened in The Hague on October 25, 1980, known as the “Hague Convention”.

*Originally published in Spanish by the Spanish newspaper el salto, this piece has been written by journalist Patricia Reguero Ríos and translated into English by Diana García. This article is the result of the work of The Hague Papers network of journalists.