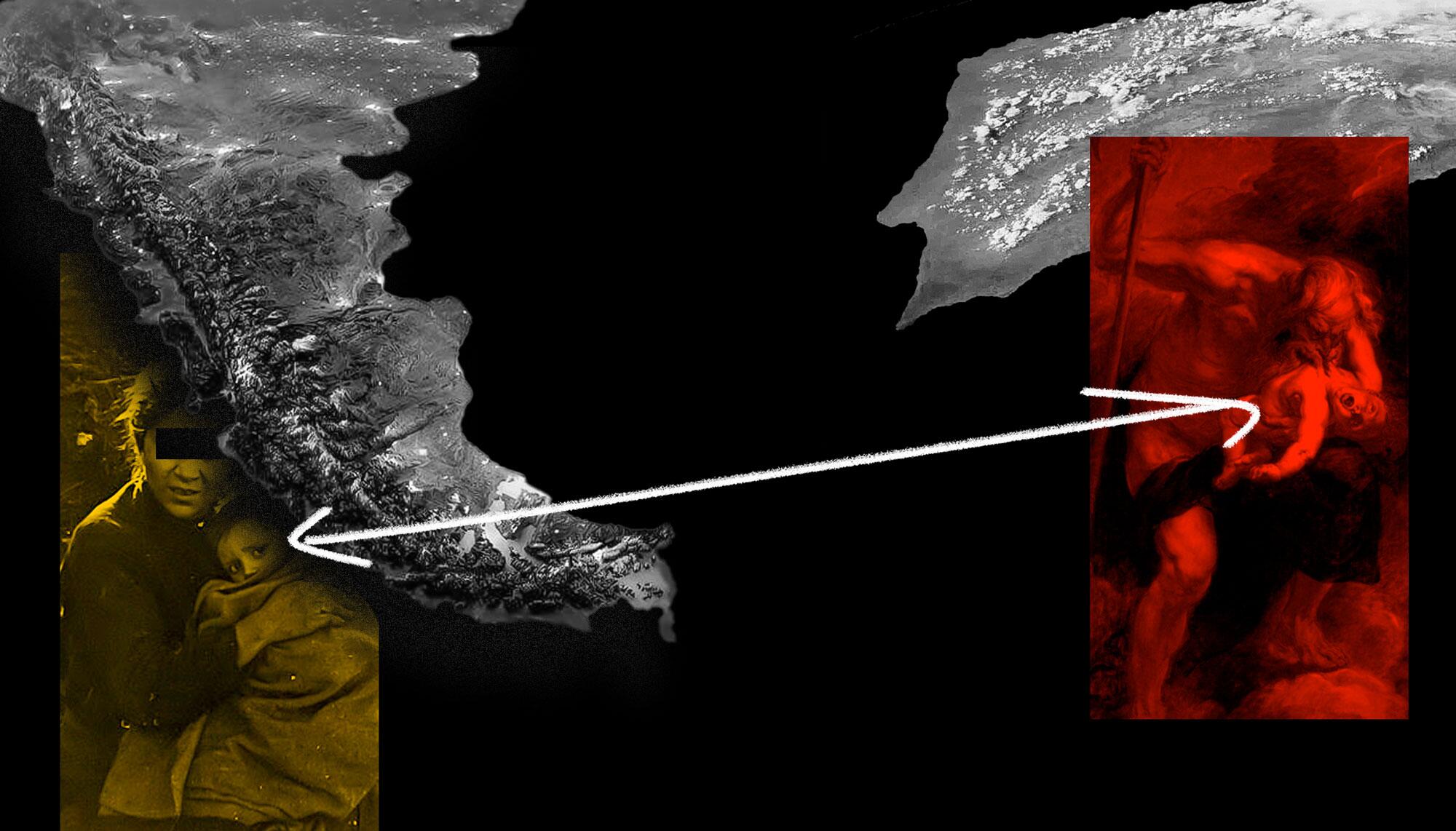

July 18, 2024. A Chilean mother hides with her son for two years while the father claims him in Spain. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child ruled in favor of the mother, but no authority has enforced this decision.

Two years have passed since the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child asked Chile to review a ruling on the return of an autistic child to Spain, where his father is claiming him. The Supreme Court of Chile ordered the transfer of the child, then almost 4 years old, invoking the Hague Convention on International Child Abduction, which provides for the immediate return of children or adolescents who are abroad with one parent without the consent of the other and without taking into consideration their circumstances. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child intervened and made history, but this has not made a difference.

In June 2022 the body responsible for safeguarding the Convention on the Rights of the Child ruled for the first time on a Hague case involving the transfer of minors. The case began in 2018, when the father of the minor filed a complaint against the mother with Spain’s Ministry of Justice for the unlawful abduction and retention of the child, under the procedure established by the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction. Since then, Chile has ignored the UN ruling, which is binding as a signatory country. The child and his mother remain hidden in a clandestine location. Meanwhile, the Chilean Police are looking for them with arrest warrants issued by the Judiciary.

Without disclosing her location, the mother shared her story in an exclusive interview with the hague papers, the global network of journalists who have put a spotlight on the consequences of applying the Hague Convention without a gender or childhood perspective. Valentina (a fictitious name) risked everything to secure the physical and mental well-being of her child in Chile. It’s a story straight out of a movie but without a happy ending.

“Valentina was accused of kidnapping her Chilean-born son by taking him from Spain, where they lived, to Chile, the mother’s country of origin, despite having authorization from the father.”

Valentina was accused of kidnapping her Chilean-born son by taking him from Spain, where they lived, to Chile, the mother’s country of origin. The father had agreed that she and the child could enter and leave Chile and stay for indefinite periods in a written authorization that stated in broad terms that she could even settle abroad with the child until he came of age.

At the time, Valentina said, the father travelled a lot for work and the marriage was “frozen” while he underwent psychological treatment for an addiction. They maintained a cordial relationship, including visitation, from August 2017 until July 26, 2018, when the father filed a complaint with the Spanish Ministry of Justice. That was when the nightmare began.

Initially, Valentina won two consecutive appeals – first in Family Court and then in the Court of Appeals – which allowed mother and son to remain together in Chile. The father, however, then took the case to the Chilean Supreme Court which ultimately ordered the child’s return to Spain. According to the UN Committee, the decision of Chile’s highest court did not consider the best interests of the child in context, a fundamental principle of child protection enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Lawyer Yohana Cornejo, who brought the case to the UN on Valentina’s behalf, believes that the purely formal arguments of the Supreme Court, which overturned the previous resolutions, violate the rights of the child. “We turned to the Committee because in Chile there is no other legal entity that allows us to correct a violation committed by the highest court,” she explained to the hague papers.

“We are still waiting for a decision and the only thing the State has said is that it does not have the means to do so, alleging the lack of legal avenues and a lack of jurisprudence on the matter,” says the woman’s lawyer.

The day the international ruling was published filled Valentina and her lawyer with hope. There was light at the end of the tunnel. However, shortly afterward, Cornejo said, it was discovered that “making it applicable in Chile was practically impossible.”

“We are still waiting for a decision and the only thing the State has said is that it does not have the means to implement it, alleging a lack of legal avenues and jurisprudence in this regard. The search warrants and pressure to hand the child over to his father have become more and more frequent, without considering any kind of context,” she added.

The binding nature of the UN opinion is complex because the Committee is not a jurisdictional body, Cornejo explained. But “international human rights treaties have a higher hierarchy in our legislation and, in accordance with article five of the Chilean Constitution, they acquire constitutional status,” the lawyer added.

Valentina’s story

“Cutting off contact with my loved ones was like ceasing to exist,” the mother confessed. “Everything I am was put on hold. It’s also like feeling stateless, because your country is looking for you as if you were a criminal.”

Valentina relived the moment when she decided not to show up for the flight that would take her son to Spain, as the Supreme Court had ordered. “It was super complicated, some told me to give up the child because there was nothing else to do, others told me not to,” she explained, her voice cracking. “I was overwhelmed.”

“I have always tried to live the right way. As cliché as it may sound, it was how I was raised,” the mother continued. “I never thought I would have to cross the border and become a criminal to defend what is right. But I couldn’t hand over my son like someone would hand over a piece of furniture. They told me that if I handed him over, the father wouldn’t know what to do with an autistic child. I thought that if I handed him over, my son would be hurt.”

If Valentina moved the child to Spain, there was no guarantee that she would be able to stay close to him as the father’s lawsuit would likely prevent her from staying in the country. There was also no guarantee that the child’s health would be safeguarded during the process of moving and adapting him to his new home. For example, the day after they arrived in Madrid, the child would be assessed to determine his level of autism.

“I explained to the Chilean court that he is a highly autistic child and would be 16 hours jet-lagged so he would not be in a condition to be assessed,” she recalled. “The doctors treating him in Chile told me that it would take him at least three months to adjust to the change.”

“The doctors prepared a guideline for the transfer process. They outlined all the care that should be taken with their son, but the mother presented the guideline to the court and the court did not even review it.”

In addition, the doctors prepared a guideline for the transfer process and outlined all the care that should be taken with their son. But when this guideline was presented to the court, they did not even review it. “I am not comparing myself, Valentina said, “but I remember a phrase from Mandela: when a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, that man has no other option than to become an outlaw.”

In such an adverse situation, Valentina must learn how to stand by her son’s side and to give him the special attention he requires. Together with his mother, the boy sings, plays and learns things, such as colors or animals. She describes him as a happy child.

“It may sound strange,” Valentina said, “but I thank God every day that he is autistic, because that way he doesn’t realize that at any moment he could be taken away. I met mothers who went through this and one of them told me that her 6-year-old son had panic attacks at night. The child couldn’t sleep without the help of medication. Every night he was afraid that they would send him to live with his father. My son doesn’t know that. He doesn’t realize it because he is autistic.”

The need to remain hidden led her to become her son’s therapist. To do so, she has taken nearly eighty distance learning courses, taught by specialists from Australia, Canada, England and the United States since there is little information in Chile. The hardest part of Valentina’s clandestine situation has been distancing herself from the people she loves and who love her. She had to cut all emotional ties, she said, because otherwise they risk being found.

“I think every day that I am doing the right thing. I have studied like crazy to help my son, because I cannot take the risk. The minute they find us, God forbid, they will put him on a plane and send him to Spain, because as the judge once told me, ‘The child will go, whether passed out, vomiting or doped, he is going.’”

Other Valentinas

Valentina’s story is more common than it seems. In fact, Cornejo also turned to the same international system for another Chilean mother, whose son was taken from her and sent to Switzerland to live with his father. That time, the UN Committee did not accept the request.

Two other examples, linked to Mexico and Portugal , led Chile’s top Children’s Ombudsman, Patricia Muñoz, to speak out against the return of minors during her administration. Sending formal opinions, or amicus curiae, to the ongoing trials, Muñoz reiterated that the Hague Convention “must be in line with other standards and, particularly, with human rights.”

She also asked the Supreme Court to take her considerations into account “in all cases of this nature.” This did not happen as Valentina’s story shows. In this regard, the former head defender told the hague papers that beyond the international level, “this situation is not consistent with the internal legislation approved in Chile since at least 2022, namely, the Comprehensive Protection and Guarantees System for Children.”

Women today are three times more affected by the treaty than men and account for 75% of international child abductions

“The rights of the father have been put above all else, without considering or addressing the needs of the child,” she claimed. For the lawyer, who is also a specialist in child protection, the treaty on abductions is obsolete and needs to be revised “in order to make restitution processes more effective.”

“This treaty was approved in 1980,” Muñoz said, “but societies have evolved, just as family relationships have evolved, and it is necessary to attend to the best interests of the child.”

Some of the cases that the hague papers has learned about in Spain include one where a Uruguayan mother lost custody to a father accused of abuse, and another one where a Dutch mother reported sexual abuses committed against her child by the Spanish father and grandfather without this complaint ever being investigated.

According to official reports, women are now three times more affected by the treaty than men, and account for 75% of international child abductions. Data from the Hague Convention specify that in 2021, the last year in which data was collected, there were 2,579 requests for restitution.

Access to Justice

Chile’s current Children’s Ombudsman, Anuar Quesille, also responded to the hague papers and regretted “the reasoning of the courts,” acknowledging that “there is still a large gap in judicial matters” to protect children and adolescents since Chile signed the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990.

In Valentina’s case, Quesille agrees with Cornejo on the “lack of sufficient arguments” on the part of the Supreme Court to justify the ruling. In his view, “the vulnerability of the child due to his autism should have been considered” as well as “the possible separation from his mother, and to what extent the restitution would expose him to physical or psychological harm, to the detriment of his best interests.”

The ruling also violates the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ratified in 2008. Since March 2023, Chile has had, in addition, a specific law to protect all people with autism spectrum disorder, including children and adolescents. This law “proposes that people on the autism spectrum be properly treated in judicial proceedings,” Gabriela Verdugo, president of the Fundación Unión Autismo y Neurodiversidad (FUAN), told the hague papers. It’s a challenge that awaits codification, she added.

The Supreme Court declined to comment on the matter, and the Ministry of Justice could not be contacted.

*Originally published in Spanish by the Spanish newspaper el salto, this piece has been written by journalist Mónica Aguilera and translated into English by Diana García.